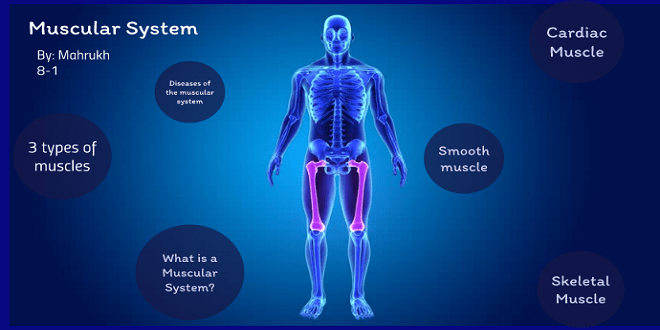

Introduction to the Muscular System

Muscle structure

All muscle cells are specialized for contraction. When these cells contract, they shorten and pull a bone to produce movement. Each skeletal muscle is made of thousands of individual muscle cells, which also may be called muscle fibers. Depending on the work a muscle is required to do, variable numbers of muscle fibers contract. When picking up a pencil, for example, only a small portion of the muscle fibers in each finger muscle will contract.

Muscle arrangements

Muscles are arranged around the skeleton so as to bring about a variety of movements. The two general types of arrangements are the opposing antagonists and the cooperative synergists.

Antagonistic Muscles

Antagonists are opponents, so we use the term antagonistic muscles for muscles that have opposing or opposite functions. The biceps brachia is the muscle on the front of the upper arm. The origin of the biceps is on the scapula (there are actually two tendons, hence the name biceps), and the insertion is on the radius. When the biceps contracts, it flexes the forearm, that is, bends the elbow.

Energy sources for muscle contraction

Before discussing the contraction process itself, let us look first at how muscle fibers obtain the energy they need to contract. The direct source of energy for muscle contraction is ATP. ATP, however, is not stored in large amounts in muscle fibers and is depleted in a few seconds.

Muscle fiber— microscopic structure

We will now look more closely at a muscle fiber, keeping in mind that there are thousands of these cylindrical cells in one muscle. Each muscle fiber has its own motor nerve ending; the neuromuscular junction is where the motor neuron terminates on the muscle fiber. The axon terminal is the enlarged tip of the motor neuron; it contains sacs of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

Contraction—the sliding filament mechanism

All of the parts of a muscle fiber and the electrical changes described earlier are involved in the contraction process, which is a precise sequence of events called the sliding filament mechanism.

Responses to exercise— maintaining homeostasis

Although entire textbooks are devoted to exercise physiology, we will discuss it only briefly here as an example of the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis. Engaging in moderate or strenuous exercise is a physiological stress situation, a change that the body must cope with and still maintain a normal internal environment, that is, homeostasis.

Aging and the muscular system

With age, muscle cells die and are replaced by fibrous connective tissue or by fat. Regular exercise, however, delays atrophy of muscles. Although muscles become slower to contract and their maximal strength decreases, exercise can maintain muscle functioning at a level that meets whatever a person needs for daily activities. The lifting of small weights is recommended as exercise for elderly people, women as well as men. Such exercise also benefits the cardiovascular, respiratory, and skeletal systems.

Major muscles of the body

When you study the diagrams of these muscles, and the tables that accompany them, keep in mind the types of joints formed by the bones of their origins and insertions. Muscles pull bones to produce movement, and if you can remember the joints involved, you can easily learn the locations and actions of the muscles.

Muscles of the head and neck

Three general groups of muscles are found in the head and neck: those that move the head or neck, the muscles of facial expression, and the muscles for chewing. The muscles that turn or bend the head, such as the sternocleidomastoids (flexion) and the pair of splenius capitals muscles (extension), are anchored to the skull and to the clavicle and sternum anteriorly or the vertebrae posteriorly. The muscles for smiling or frowning or raising our eyebrows in disbelief are anchored to the bones of the head or to the undersurface of the skin of the face.

Last word

The hip muscles that move the thigh are anchored to the pelvic bone and cross the hip joint to the femur. Among these are the gluteus Maximus (extension), gluteus mediums (abduction), and iliopsoas (flexion). The muscles that form the thigh include the quadriceps group anteriorly and the hamstring group posteriorly. For most people, the quadriceps is stronger than the hamstrings, which is why athletes more often have a “pulled hamstring” rather than a “pulled quadriceps.”